Magic mushrooms, a psychedelic drug that has been classified as a Schedule I substance for decades, might soon become a valuable tool in psychiatry, thanks to scientists at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. These researchers were pioneers in the field of psychedelic therapy and they have taken the first steps towards harnessing the beneficial effects of magic mushrooms in the treatment of mental health disorders. This essay will delve into the recent breakthrough at Johns Hopkins and examine the potential benefits of using magic mushrooms as a medicine.

Earlier this year, the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins announced the launch of a new study that will examine whether psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, has therapeutic potential for anorexia nervosa. This study is part of a new wave of research that is investigating the use of psychedelics as a treatment for various mental health disorders.

The research team at Johns Hopkins has previously conducted studies on the use of psilocybin to treat depression, anxiety, and addiction. In these studies, they found that psilocybin was effective in reducing symptoms of these conditions, even in patients who had previously been resistant to treatment. The team’s previous work has received widespread recognition, and it is clear that they are at the forefront of the psychedelic therapy movement.

The potential benefits of using magic mushrooms as medicine go beyond traditional treatments. While conventional psychiatric medications can take weeks or even months to take effect, psilocybin has been shown to have a rapid and long-lasting impact on mental health. In addition, research has found that psilocybin can assist in reducing existential fear and anxiety in people with terminal illnesses, and can even result in positive personality changes.

Of course, the use of magic mushrooms in medicine is not without its controversies. There are concerns over the potential for abuse, and the need for proper medical supervision during psilocybin therapy sessions. However, by treating psilocybin with the same caution as any other medication, the benefits of magic mushrooms as a medicine can be maximized.

In conclusion, the recent announcement by Johns Hopkins researchers marks a major step forward in the use of magic mushrooms as a medicine. Their work has demonstrated the potential of psilocybin to revolutionize the treatment of mental health disorders. While there are still many issues to be addressed, it is clear that the effective use of magic mushrooms in medicine could have substantial benefits for our society’s mental health.

Just a few decades ago, the approach would have been unfathomable to many. Using psychedelic drugs to treat people with PTSD? Depression? Addiction? To make them stop smoking? To perhaps treat Alzheimer’s? Wow. Just say no. Weren’t these the drugs we were told growing up gave you emotional disorders? But times have changed, and today, as with so many other cultural shifts, people are taking a second look at some of the things considered taboo not so long ago. And it just could be that the same generation that popularized the drugs could benefit from their therapeutic potential.

Getty

Roland R. Griffiths, Ph.D., a psychopharmacologist and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Department of Neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said in an interview that the approach could offer “an entirely new paradigm for treating psychiatric disorders.”

Types of Research Chemicals and Their Importance – Plant Feed Shop

He should know. Griffiths initiated the psilocybin research program at Johns Hopkins almost 20 years ago and led studies investigating the effects of its use by healthy volunteers. His research group at Johns Hopkins was the first to obtain regulatory approval in the U.S. to re-initiate research with psychedelics in psychedelic-naïve healthy volunteers in 2000. Griffiths said his group’s 2006 publication in the journal Psychopharmacology on psilocybin is widely considered the landmark study that sparked a renewal of psychedelic research world-wide.

Roland Griffiths, Ph.D., director, Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns … [+]

(Photo courtesy of Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research)

Since then, Griffiths and his team have published several groundbreaking studies in more than 60 peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals. In fact, scientists at Johns Hopkins have administered psilocybin to over 350 healthy volunteers or patients over the past 19 years in some 700 sessions.

Griffiths will head up the new Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine. The first of its kind in the U.S. and the largest research center of its kind in the world, the center is being funded initially by a $17 million donation from a group of private donors to advance the emerging field of psychedelics for therapies and wellness. The center will house a team of six faculty neuroscientists, experimental psychologists and clinicians with expertise in psychedelic science, as well as five postdoctoral scientists. Graduate and medical students who want to work in psychedelic science, but have had few avenues to study in such a field, will be trained at the center.

“We have to take braver and bolder steps if we want to help those suffering from chronic illness, addiction and mental health challenges,” Alex Cohen, president of the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation and a center-funder, said in a statement. “By investing in the Johns Hopkins center, we are investing in the hope that researchers will keep proving the benefits of psychedelics — and people will have new ways to heal.”

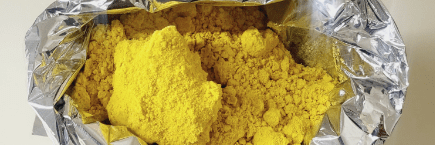

Psychedelics are a class of pharmacological compounds that produce unique and profound changes of consciousness. The most common psychedelics are psilocybin, , LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), DMT (dimethyltryptamine), and mescaline. Much of Griffiths’ work is focused on psilocybin, the chemical found in so-called magic mushrooms.

Although research with these compounds began in the 1950s and 1960s in America, Griffiths said it was the “cultural trauma” of the psychedelic 60s—which included some adverse effects of the compounds—that ended it in the early 1970s. The unfavorable media coverage that ensued resulted in misperceptions of the risks of the drugs and highly restrictive regulations.

There are no federal funds being allocated to the new center. “There has been almost no funding for [psychedelic therapeutic research in people] because we are stuck in the mindset of the 1960s,” Griffiths said. “Psychedelics were demonized. Their use was associated with the anti-war and anti-establishment movements of the 1960s and viewed as culturally disruptive. The sensationalistic media coverage established a narrative that overestimated risks that was soaked up by the culture. It takes a long time to dispel such a narrative.”

With the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, Johns Hopkins reports it is the leading psychedelic research institution in the U.S., and among the few leading groups worldwide. “Research by us and others suggests therapeutic effects in people who suffer a range of challenging conditions including addiction (smoking, alcohol, other drugs of abuse), existential distress caused by life-threatening disease, and treatment-resistant depression. Studying healthy volunteers has also advanced our understanding of the enduring positive effects of psilocybin and provided unique insight into neurophysiological mechanisms of action, with implications for understanding consciousness and optimizing therapeutic and non-therapeutic enduring positive effects,” the center reports.

“There is much work to be done,” Griffiths said, adding that researchers want to next study the effects of psychedelics in people with early Alzheimer’s disease. “To the extent that these drugs produce neuroplasticity, there may be some enduring effects on cognitive process,” he said. That is in the future, he said, but for now, at least they know they can help the depression that comes with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Griffiths said researchers have demonstrated in one treatment session with psychedelics what years of psychotropic drugs and counseling have not been able to accomplish. He compared psychedelic treatments for psychiatric problems to a curative surgical procedure (e.g. joint replacement)—a one-time treatment that changes everything. “Many in the psychiatric community are baffled by this approach because we do not have any acute treatments that produce such robust and enduring therapeutic effects. Frankly, it seems too unbelievable to be true, but yet the results to date suggests such efficacy,” he said.

People who have been treated with psilocybin often rate their encounters with psilocybin as among the “most personally meaningful experiences of their entire lives,” Griffiths said. “It is fundamentally different than any other psychoactive drug. Because these experiences occur in most people, studies often look very similar to naturally-occurring experiences, and they appear to be biologically normal. That is, we seem to be wired to have such experiences.”

“Some would hold that we were evolutionarily selected for such experiences because it results in some survival advantage.” Griffiths says that some people interpret the experience as an encounter with ultimate reality or with God.

And the drugs seem to offer neuroplasticity, or the ability of the brain to change, he said, allowing people to get out of the habitual ruts they have put themselves in as new neuropathways are formed. Griffiths said people claim that “it feels like a home-coming or an epiphany that allows them to rewrite the narrative of their lives.”

Griffiths said he has administered psilocybin to individuals who have received a life-threatening diagnosis of cancer and individuals with treatment-resistant depression. “There were large and enduring decreases in their depression, and it endured past six months,” he said.

And some 80% of patients who have been treated for nicotine addiction are still smoke-free six months later, he said. There are other investigators looking at alcohol and cocaine addiction. And other notable educational institutions are studying the possibilities of therapy with psychedelics, he said, including New York University (NYU), Yale University (YU), University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), University of California, San Fransisco (UCSF) and University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison).

Griffiths said that researchers are beginning to have hope that the compounds can be used in many more ways in a variety of maladies. “It appears as though the effects may be transdiagnostic—that they may be able to treat a variety of different disease entities including psychological and behavioral disorders,” he said.

For now, the center will focus on how psychedelics affect behavior, brain function, learning and memory, the brain’s biology and mood, Johns Hopkins announced last week. “Studies of psilocybin in patients will determine its effectiveness as a new therapy for opioid addiction, Alzheimer’s disease, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (formerly known as chronic Lyme disease), anorexia nervosa and alcohol use in people with major depression. The researchers hope to create precision medicine treatments tailored to individual patients’ specific needs.”

Griffiths said volunteers for Johns Hopkins’ studies have been thoroughly screened, and he discourages people from attempting to self-medicate with psychedelics on their own. The center’s studies are done under carefully controlled circumstances, with known doses and trained therapists at participants’ sides for after care.

He said the concentration of street drugs is unknown, they could contain other contaminants, and some chemicals may be toxic and severely dangerous.

Additionally, Griffiths emphasized that not everyone should receive these drugs. People who are prone to psychosis, such as schizophrenia, and other serious psychiatric conditions, may be vulnerable to enduring adverse effects. Furthermore, there is concern that individuals may put themselves or others at risk by taking psychedelics on their own. “In a clinical setting, we can mitigate those risks,” he said.

According to officials, the new center’s operational expenses for the first five years will be covered by private funding from the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation and four philanthropists: Tim Ferriss (author and technology investor), Matt Mullenweg (co-founder of WordPress), Blake Mycoskie (founder of TOMS, a shoe and accessory brand) and Craig Nerenberg (investor).

James Potash, M.D. called the investors “enlightened” in a statement. “This centre will allow our enormously talented faculty to focus extensively on psychedelic research, where their passions lie and where promising new horizons beckon,” the Henry Phipps Professor and director of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Johns Hopkins said.

Contact US Now

Telegram Channel: https://t.me/cannabinoidssaless

Telegram Number: +1 (413) 258-1154

Telegram Username: cannabinoidssale

Whatsapp: +1 (413) 258-1154

Email: healthcareltfse@gmail.com

Wickr: bestchemsales